Control stands apart from most music biopics because it refuses to turn Curtis into a simple icon or legend. Instead of building toward a triumphant performance or a tidy moral, the film lingers on the small spaces where Curtis’s life actually unfolded–small homes, rehearsal rooms, backstage hallways, and hospitals.

Kenneth Anger’s “Lucifer Rising” and the Ritual of Becoming

Kenneth Anger considered cinema not as storytelling but as an act of Magick in the tradition of Aleister Crowley’s “art and science of causing change in accordance with one’s will.” The film is not meant to explain itself. Its creator believed that meaning, like ritual, is experiential; it is something the viewer feels, not interprets.

The Third Film – all images copyright Estate of Kenneth Anger. No unauthorized reproduction.

There are films whose production histories feel like myths unto themselves, works that must die and be resurrected before they can truly be said to exist. Lucifer Rising is one of those films. It is one of the great Third Films of cinema: the version that exists after the screenplay, after the imagined production in the director’s head, after failures and fallings-out and vanished collaborators. It is the film that survives the ordeal of becoming.

In his 2007 DVD commentary, Kenneth Anger explains that the version we know today is the second Lucifer Rising. The first version “came to nothing” after his falling-out with Bobby Beausoleil, the radiant nineteen-year-old protégé who once lived with Anger, acted in his earliest rituals, and then fell tragically and irrevocably under the influence of Charles Manson. Years later, while Beausoleil served time for murder in a California prison, the two men reconciled. Behind bars, Beausoleil composed and recorded a new score with twelve incarcerated musicians. Out of catastrophe and ruin, a new film emerged.

It is impossible to talk about Lucifer Rising without talking about who Kenneth Anger gathered around himself. The first Lucifer was Beausoleil: an angelic presence with shoulder-length hair, piercing eyes, and a top hat, briefly a member of Arthur Lee’s seminal psychedelic band, Love. Anger saw in Beausoleil the mythic, the fallen, the divine. Their break came over drugs. Despite his embrace by the counterculture, Anger rejected the “psychedelic” label outright. “Lucifer Rising is not psychedelic,” he insisted. “It’s a film by Kenneth Anger.”

Image description: L.M. Kit Carson as David Holzman in David Holzman’s Diary.

That said, it’s a film made by other people too, people whose influence can be felt across the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. Michael Cooper, the photographer behind the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, captured the film’s glowing images. Chris Jagger, Mick Jagger’s younger brother, briefly played the High Priest before Anger dismissed him for asking too many questions. And Jimmy Page, a fellow devotee of Aleister Crowley, composed the original score and even appears onscreen admiring a portrait of the Great Beast. Page came to Anger’s attention when he outbid Anger at Sotheby’s for a Crowley book. To his dismay, Page’s submitted score was only half as long as the film; was he supposed to restart it in the middle?

And yet, Lucifer Rising without Beausoleil’s score isn’t Lucifer Rising at all. Everything, it seems, had to have happened for a reason.

The trail of alliances and breakages is riveting: from Page outbidding Anger at Sotheby’s for a Crowley book, to Beausoleil’s score emerging from within a prison, to Anger selling his air conditioner in 1981 because finishing the film had cost him everything; these footnotes are almost as interesting as the film itself. Anger’s life, like the rituals he staged, was marked by both glamour and ruin.

Magick, Will, and Cinema as Ritual

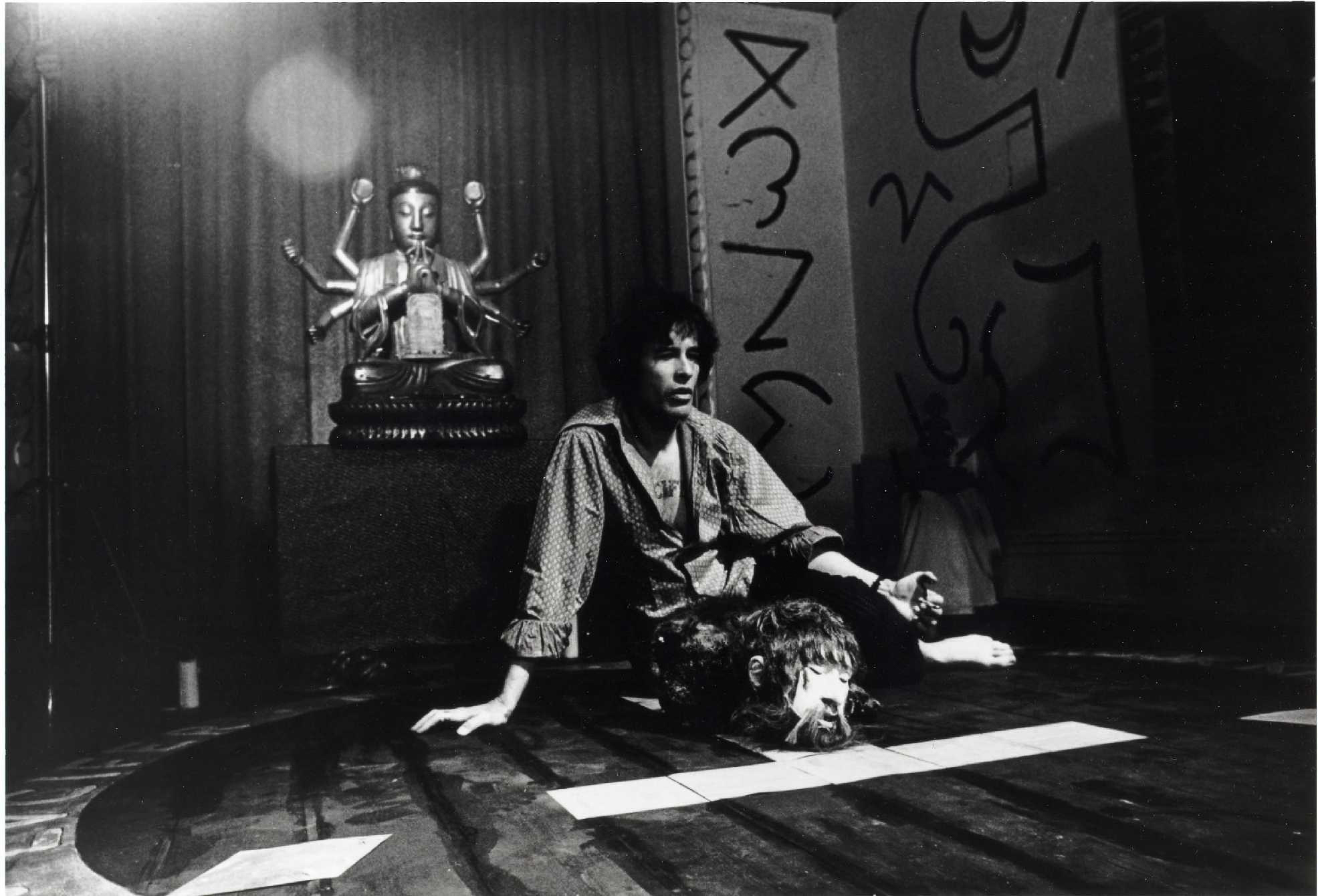

Image:Marianne Faithfull as Lillith in Lucifer Rising

Kenneth Anger considered cinema not as storytelling but as an act of Magick in the tradition of Aleister Crowley’s “art and science of causing change in accordance with one’s will.” The film is not meant to explain itself. Its creator believed that meaning, like ritual, is experiential; it is something the viewer feels, not interprets.

Anger once called cinema “an evil medium,” joking (or not) that filming was merely a pretext to “capture people.” Considered in this light, Lucifer Rising is an invocation, a poetic broadcast signal sent across time and space.

Even the uninitiated will sense that something ceremonial is unfolding in Lucifer Rising. Anger and his collaborators traveled to locations that vibrate with ancient power: the pyramids of Giza, Stonehenge, the Externsteine in Germany, Icelandic volcanoes. These are places where history feels thin, where the membrane between worlds loosens, where the gods might plausibly reveal themselves and speak.

The film opens with a volcanic eruption: creation and destruction fused in a single, primordial gesture. Across the globe, mythic figures begin to signal to one another as if awakening from different eras simultaneously. Isis, portrayed by Myriam Gibril, removes an ankh from a temple wall. the life source calling out across time. Osiris, played by the “death-haunted” director Donald Cammell, receives her message like a transmission from another realm. In two of Cammell’s greatest films, the protagonists shoot themselves in the head (one of them portrayed by Mick Jagger himself), and Cammell himself ended his life in the same fashion. Yet another instance of Anger’s casting choices blurring the border between symbol and reality.

Lilith, played by the singer Marianne Faithfull, rises from her tomb beside a river, grey with night, fog, and discontent, the jilted consort who was meant to marry Lucifer but was rejected. Her emergence is one of the film’s most powerful images. Arms open, she steps forth from temple to desert in a gesture that feels like an embrace of the universe. She repeats the gesture again at the feet of the Sphinx, invoking a cosmic longing that spans millennia.

Lucifer mirrors her signal back from Stonehenge. Through the magic of the cut, their gestures collapse time, revealing that what Anger has been intercutting is not chronological but spatial. All the characters in Lucifer Rising consort across eras, nations, and mythologies to bring about Lucifer’s ascent: a choreography of awakening, unfolding on multiple planes at once.

Here, Lucifer is not the Christian devil. Crowley’s poem, “Hymn to Lucifer,” celebrates Lucifer as the light-bringer. For the Romans, the morning star of Venus, herald of the dawn, was known as Lucifer. Anger speaks to this luminous cosmology, the eternal communication between life and death, not a moral contest between good and evil. Myth thrives on dualities, where life and death are intertwined, whereas Anger felt Christianity flattened these dual realities into simplistic binaries.

The High Priest, played by Mick Jagger’s younger brother Chris, appears briefly after a volcano is superimposed onto a pyramid. His presence didn’t last long. “He kept asking what it means,” Anger shrugged. “It’s too complex and deep. Unless you’re an initiate, and then it’s simple, almost like a childish fairy tale.”

Triangles and circles echo throughout the film, recurring sigils of magick. A glass wand, the Egyptian solar disc, ancient stelae; Anger links these symbols to the modern mythology of flying saucers. The UFOs that appear near the end are based on actual lights in the sky witnessed by the cast and crew at dawn during production. Anger delights in this. “Thank God we have mysteries in life,” he remarks. “No matter how much science can explain, there will always be mysteries. And that’s what makes life fascinating to me. I certainly don’t want the answers to everything.”

The Externsteine, a cluster of tall, jagged sandstone pillars rising from a forest in northwest Germany, is one of the most symbolically charged landscapes in Europe. Its stones look unnatural, almost sculpted, but their forms are geological, carved by ice and wind, then carved again by human hands over centuries. There are spots where the sun aligns during the solstices with carved openings, a hallmark of ancient ritual architecture. Its recent history is more troubled; the Nazis used the site to induct Hitler Youth, presenting sacred daggers during rituals staged on the Externsteine’s stone bridges. Anger, ever attuned to the continuity of symbols (and their corruption) incorporates this history into the film’s charged atmosphere. Through Anger’s film, the site becomes a literal and symbolic network where energies move between worlds. Anger’s intercutting between the Externsteine, the pyramids, and Stonehenge illustrates that all these sites are activated in the same ritual transmission.

Once Lilith ascends the Externsteine and finds the solar portal through which light passes only on the solstice, the film’s energy shifts. The music accelerates. The magic circle ritual begins. Magic circles are meant to dispel chaos; here Anger, the Magus, rounds the circle, summoning a vortex of will and myth.

Lucifer appears in the form of Leslie Huggins, whom Anger once described, half-seriously, as “an authentic demon in human form.” Jimmy Page, meanwhile, holds the Egyptian Stele of Revealing, the artifact Crowley believed predicted the rise of Thelema, his religion of the will.

Even if the viewer lacks the tools to appreciate every dimension of Anger’s magick, the film moves with undeniable momentum. Lucifer and Lilith mirror each other’s gestures across continents. Mythic forces converge. A new age is heralded in light, shadow, and flame.

And then, because this is Kenneth Anger, the red UFOs arrive.

Does it make literal sense? Possibly, if one is tuned to Thelemic frequencies. But even without that tuning, the transmission is unmistakable.

Film still – copyright Estate of Kenneth Anger

Near the conclusion of the film, a long static shot of two Egyptian colossi lingers on the screen. This is the longest cut in the film and possibly Anger’s entire oeuvre, far longer than he typically allows. In the deep background, almost imperceptible, a small fire grows. Without the director telling us in his commentary, we’d likely never know; but the fire is Kenneth Anger burning his screenplay.

It is a fitting ending for Lucifer Rising: a ritual sacrifice of the first and second films, leaving only the third: the one that survived discord, betrayal, imprisonment, occult devotion, and Anger’s own mercurial will.

The film that remains is not cinema in the usual sense. It is an act of becoming, a cinematic invocation forged from the ruins of friendship, the disciplines of ritual, and the persistence of myth.

Anger did not merely complete a film. He performed one.

In the case of Lucifer Rising, the performance never really ends.

MATTHEW CARON

Kenneth Anger considered cinema not as storytelling but as an act of Magick in the tradition of Aleister Crowley’s “art and science of causing change in accordance with one’s will.” The film is not meant to explain itself. Its creator believed that meaning, like ritual, is experiential; it is something the viewer feels, not interprets.

Ondi Timoner has a singular talent for capturing lighting in a bottle. Her body of work is full of indelible portraits of figures who capture a moment in time, and often they are characters that no one else would have thought to follow, or could endure following.

It’s a miracle that someone like Wadleigh wound up in charge of the massive enterprise of Woodstock, and it endures because it is the work of someone with a romantic poet’s sensibility, rather than Hollywood or Madison Avenue.

The Hi-Desert Cultural Center is proud to present a special screening of ENO, the first-ever generative documentary film in a one-night-only event featuring an introduction by Orian Williams, one of the revolutionary film’s producers.

Elvis, the award-winning 2022 musical spectacle by master showman Baz Luhrmann, remains fresh and vital in 2025. Looking back at the criticism of the film, high praise as well as dim dismissal, everyone seems to have undersold the theme of the artist as chattel in the entertainment industry, which has only become more urgent in the two years since.

No event found!