The film, Deep Listening: The Story of Pauline Oliveros, emphasizes something that feels especially urgent now; Oliveros’s belief that listening can be healing—not in a shallow, slogan-like way, but in the practical way that true listening reduces violence and restores healthy curiosity, as it makes room for complexity, diversity, and difference. The director calls her message one of “healing, unity and unbridled creative expression,” and the film treats that message not as sentimental inspiration, but as a discipline. Oliveros’s listening wasn’t naive. It didn’t pretend the world was already harmonious. It insisted that harmony—real harmony—requires attention, patience, and relationship.

The Radical Practice of Listening

The film, Deep Listening: The Story of Pauline Oliveros, emphasizes something that feels especially urgent now; Oliveros’s belief that listening can be healing—not in a shallow, slogan-like way, but in the practical way that true listening reduces violence and restores healthy curiosity, as it makes room for complexity, diversity, and difference. The director calls her message one of “healing, unity and unbridled creative expression,” and the film treats that message not as sentimental inspiration, but as a discipline. Oliveros’s listening wasn’t naive. It didn’t pretend the world was already harmonious. It insisted that harmony—real harmony—requires attention, patience, and relationship.

In a culture that rewards speed—fast reads, fast takes, fast responses, and fast conclusions, Deep Listening: The Story of Pauline Oliveros asks for something quietly radical…time. Not just time to watch a film, but time to notice what’s already happening around us—the vibration of the room, the distance between the words, the way other people’s lives sound when one stops working to be the loudest thing in them. That request is the heart of the movie, and it’s the heart of its subject, Pauline Oliveros.

The film is called Deep Listening for a reason. “Deep Listening” is not a genre or a brand; it’s a way of being. Oliveros used the phrase to describe listening that is expansive and embodied—listening that includes the sounds you expect and the ones you don’t, the sounds outside you and the ones inside you—breath, memory, emotion, and instinct. In Oliveros’s world, listening isn’t passive. For Oliveros, listening wasn’t only an artistic method—it was a way to practice inclusion—to make room for others, and to build community through attention. It’s creative. It’s ethical. It’s communal. It changes what you think you know.

Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) was a pioneering American composer, accordionist, teacher, inventor, and community-builder whose influence runs through contemporary experimental music, electronic music, and sound art. She also pioneered the use of recording and signal-processing technology as a living instrument—especially through tape-delay experiments and her Expanded Instrument System (EIS). Rather than using electronics as simple “effects,” EIS creates a performance environment of delays, routing, microphones, and multichannel sound that expands acoustic instruments into immersive space. In that environment control is shared, where the performer shapes the system, yet the system also shapes the performer. But describing Oliveros only in professional terms misses the point—because she didn’t treat music as a product. She treated it as a practice of attention, and attention as a form of care. Her work wasn’t about showing off what a composer could control; it was about discovering what becomes possible when people listen—fully, patiently, and together.

The documentary’s director, Daniel Weintraub, makes something clear from the beginning; this wasn’t a detached film project where the camera stays “objective” but, rather, it was a relationship—one that shaped the film’s sentiment. In the director’s own words, meeting Oliveros felt like meeting “the person who would inspire me throughout the inevitably lengthy process of making a film,” and it came with “an instant obligation to share the story of this incomparable sonic icon.” That sense of obligation matters, because Oliveros’s story isn’t just a biography; it’s a continuing invitation.

Weintraub followed Oliveros for nearly three years—through workshops, rehearsals, performances, recording sessions, and community gatherings, capturing not only what Oliveros did, but also how people changed in her presence.

Pauline Oliveros, © Ione, © Photo: Heroku Iked

That’s the part to which I keep returning—Oliveros wasn’t only a great artist, she was the kind of artist who made other people feel more alive, more capable, and more welcome inside their own individual creativity. The director describes watching her inspire “an expansive creativity” in her community, and the film seems built to show that inspiration as something concrete. Her work was a lived phenomenon especially evident in the way artists speak about her, in the way rooms rearrange themselves when she enters, and in the way listening becomes a shared event rather than an individual skill.

Pauline Oliveros came of age in the 1950s as a woman who identified herself as lesbian. In artistic environments that often treated women as exceptions, and lesbian people as something to hide, she faced obstacles that weren’t merely personal—they were structural. What is powerful is how she responded. Not by shrinking her vision to fit the room, but by expanding the room until more people could breathe inside it. She made work that didn’t just ask for inclusion; it modeled it. Her pieces often welcomed nontraditional performers and invited participation, thus blurring the line between “artist” and “audience” in ways that emphasized her conviction that creativity belongs to everyone.

Courtesy – Center For Contemporary Music Archive: Bill Maginnis, Tony Martin, Ramon Sender, Mort Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros, 1960

That conviction shows up in one of Oliveros’s most famous statements, quoted by the director,

“I never tried to build a career, I only tried to build a community.” – Pauline Oliveros

It’s hard to read that and not feel the contrast with how the majority are trained to think—about success, visibility, and achievement. Oliveros’s measure was different. If her work traveled the world (which it did), it wasn’t because she chased status. It was because her ideas were useful—deeply and humanly. They helped people make sense of themselves and each other, and continue to do so today.

The film also emphasizes something that feels especially urgent now; Oliveros’s belief that listening can be healing—not in a shallow, slogan-like way, but in the practical way that true listening reduces violence and restores healthy curiosity, as it makes room for complexity, diversity, and difference. The director calls her message one of “healing, unity and unbridled creative expression,” and the film treats that message not as sentimental inspiration, but as a discipline. Oliveros’s listening wasn’t naive. It didn’t pretend the world was already harmonious. It insisted that harmony—real harmony—requires attention, patience, and relationship.

One detail from the director’s statement deepens that sense of care. He writes that it felt crucial when making a film about someone who revered and centered listening, to “be an editor who listens.” That line sticks, because it acknowledges the challenge of filming sound to reflect listening as Oliveros intended it—you can’t just tell an audience that listening matters; you have to make them feel it. The director’s background as a recording engineer becomes part of the film’s moral logic—sound isn’t decoration here—it is the subject. The film doesn’t treat audio as something to tidy up behind dialogue. It treats sound as a living environment the viewer is invited and encouraged to enter.

And then there is the tenderness of the latter collaboration. After they met, Oliveros invited the director into her work—mixing recordings and capturing sessions, including what became her final recording with beloved collaborators. These aren’t celebrity anecdotes. They show the way Oliveros worked, through trust, through shared labor, and through friendship that isn’t separate from art…but woven into it.

What I ultimately take from Deep Listening is not just admiration, but a kind of personal challenge. The film makes it difficult to keep living as if listening is optional. It makes me wonder what I’ve been missing—what people have been trying to say under the surface of conversation, what places sound like when I stop rushing through them, what parts of myself become audible when I’m no longer “performing” in life. Oliveros’s legacy isn’t only in compositions or institutions; it’s in the countless people who learned, through her, that attention can be an act of love. That’s why this film matters. While it preserves the story of a major American cultural figure, it also keeps her community open. It extends her practice outward, toward the viewer. It doesn’t just document Pauline Oliveros; it quietly recruits you into her mission.

If you watch Deep Listening, you might come for the portrait of an extraordinary artist. But you’ll leave with something more intimate: a renewed sense that the world is speaking all the time, and that your life—your relationships, your creativity, your capacity for understanding—depends on whether you choose to hear it.

And once you’ve experienced Pauline Oliveros’s way of listening, it’s hard to go back.

ANNE SHOLTZ

Control stands apart from most music biopics because it refuses to turn Curtis into a simple icon or legend. Instead of building toward a triumphant performance or a tidy moral, the film lingers on the small spaces where Curtis’s life actually unfolded–small homes, rehearsal rooms, backstage hallways, and hospitals.

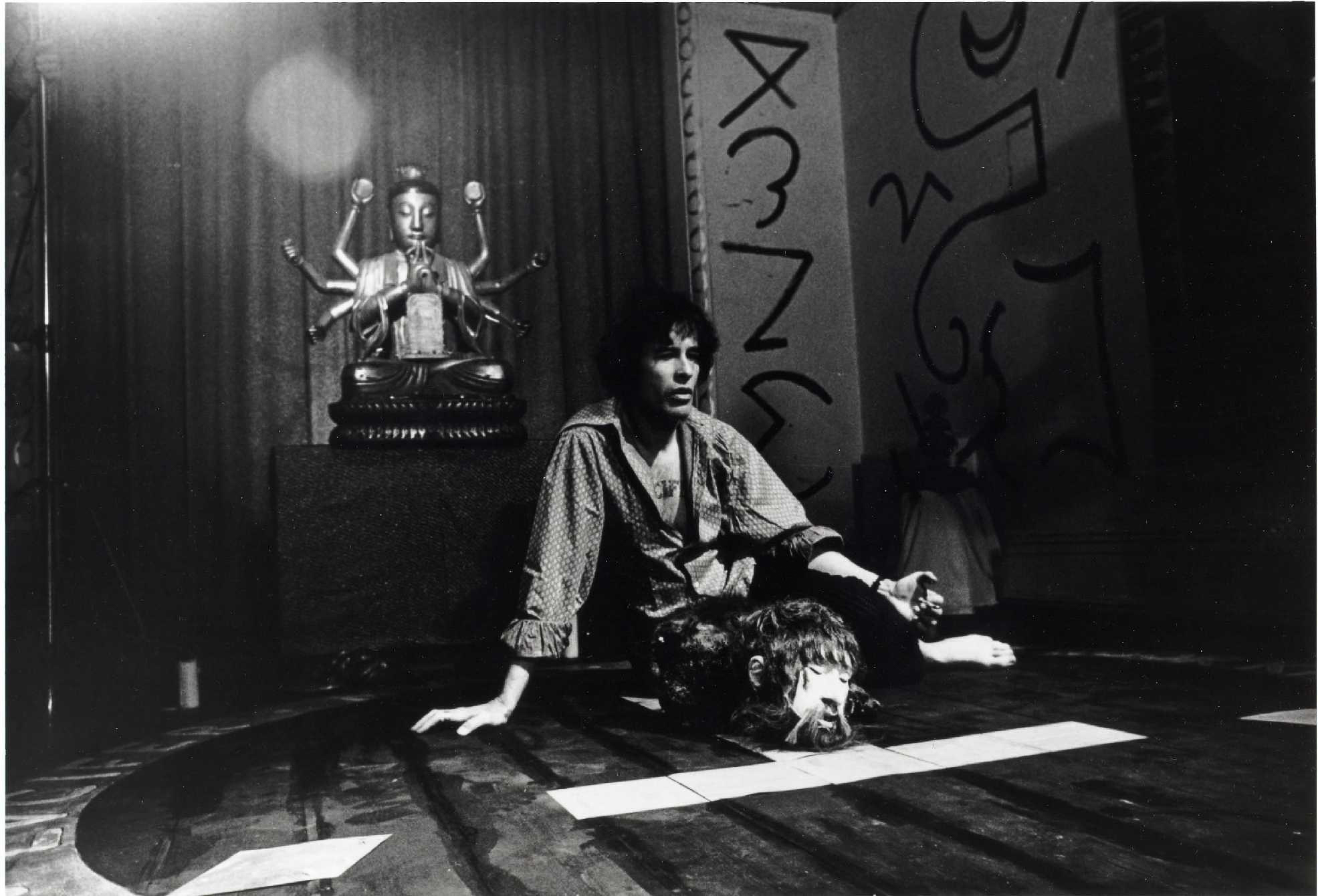

Kenneth Anger considered cinema not as storytelling but as an act of Magick in the tradition of Aleister Crowley’s “art and science of causing change in accordance with one’s will.” The film is not meant to explain itself. Its creator believed that meaning, like ritual, is experiential; it is something the viewer feels, not interprets.

Ondi Timoner has a singular talent for capturing lighting in a bottle. Her body of work is full of indelible portraits of figures who capture a moment in time, and often they are characters that no one else would have thought to follow, or could endure following.

It’s a miracle that someone like Wadleigh wound up in charge of the massive enterprise of Woodstock, and it endures because it is the work of someone with a romantic poet’s sensibility, rather than Hollywood or Madison Avenue.

The Hi-Desert Cultural Center is proud to present a special screening of ENO, the first-ever generative documentary film in a one-night-only event featuring an introduction by Orian Williams, one of the revolutionary film’s producers.

No event found!